Introduction

Ostertagia in animals is of nematodes that primarily affect small and large ruminants, causing severe parasitic gastritis. This condition is particularly prevalent in temperate climates and subtropical regions with winter rainfall.

Hosts and Site of Infection

Hosts: Ruminants (Cattle, Sheep, and Goats)

Site of Infection: Abomasum

Common Species

Ostertagia ostertagi – Cattle

Teladorsagia circumcincta – Sheep and Goats

Ostertagia trifurcata – Sheep and Goats

Minor species include O. lyrata, O. kolchida (cattle), and O. leptospicularis (cattle, sheep, and goats).

Distribution

Ostertagia species are distributed worldwide, with O. ostertagi being particularly significant in temperate climates.

Morphology

Adult worms are slender and reddish-brown, reaching up to 1 cm in length. They reside on the abomasal mucosa and can be difficult to detect without close inspection. Larvae develop within the gastric glands and are only visible microscopically.

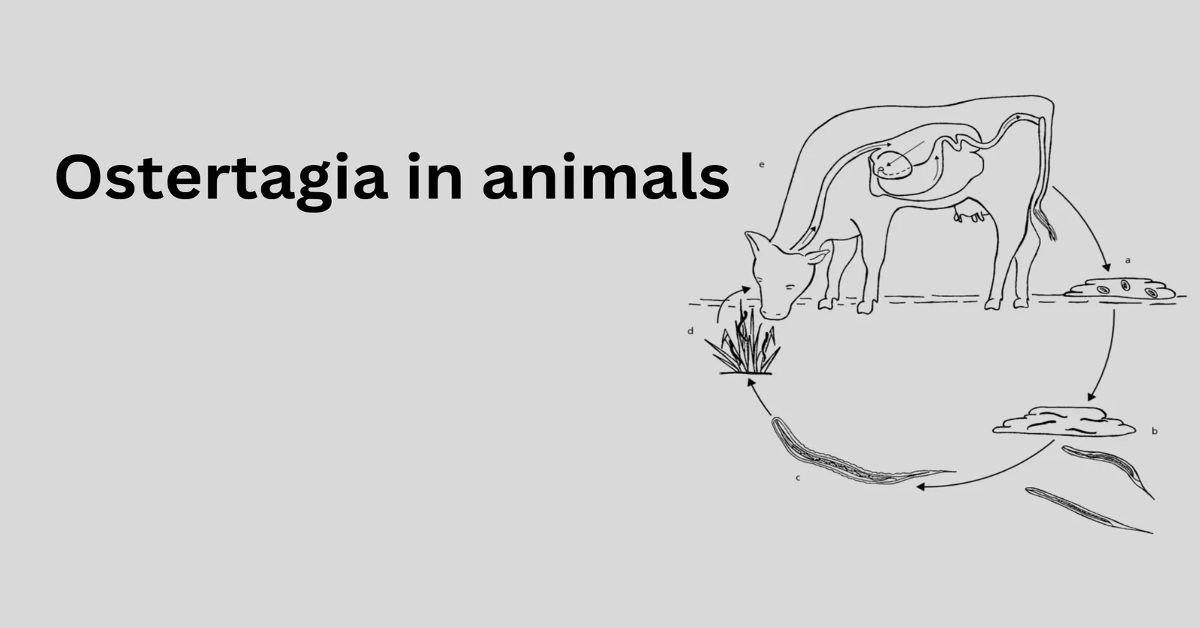

Life Cycle

Ostertagia ostertagi follows a direct life cycle:

Eggs are passed in feces and hatch into first-stage larvae (L1) in the environment.

Larvae develop into the infective third stage (L3) under favorable moist conditions.

Ruminants ingest L3, which then exsheath in the rumen and migrate to the abomasum.

Two parasitic molts occur before the larvae emerge as adults after approximately 18 days.

Under certain conditions, larvae may enter an arrested (hypobiotic) state in early L4 for up to six months.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Ostertagia Infection

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Causative Agent | Ostertagia ostertagi (in cattle), Ostertagia circumcincta (in sheep and goats) |

| Site of Infection | Abomasum (true stomach) |

| Transmission | Ingestion of infective third-stage larvae (L3) from contaminated pasture |

| Clinical Signs | – Chronic diarrhea – Weight loss – Reduced appetite – Dull coat – Submandibular edema (bottle jaw) – Poor productivity |

| Types | – Type I Ostertagiasis: Young animals during first grazing season; high worm burden – Type II Ostertagiasis: Older animals; hypobiotic larvae resume development after winter |

| Diagnosis | – Fecal egg count (FEC) using McMaster method – Fecal larval culture to identify species – Serum pepsinogen levels (↑) – Necropsy: thickened abomasal mucosa with nodules (Moroccan leather appearance) |

| Differential Diagnoses | See table below |

Differential Diagnosis Table

| Condition | Causative Agent | Clinical Signs | How to Differentiate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haemonchosis | Haemonchus contortus / H. placei | Anemia, weakness, bottle jaw | Pale mucous membranes, less diarrhea, fluke-like eggs |

| Trichostrongylosis | Trichostrongylus spp. | Diarrhea, weight loss | Affects small intestine, milder symptoms, larval ID on culture |

| Cooperiosis | Cooperia spp. | Poor weight gain, mild diarrhea | Often in calves, mild disease, co-infection with Ostertagia common |

| Liver Fluke (Fasciolosis) | Fasciola hepatica | Anemia, bottle jaw, poor growth | Liver damage on palpation or necropsy, fluke eggs in feces |

| Coccidiosis | Eimeria spp. | Bloody/mucoid diarrhea, straining | Seen in young animals; oocysts in feces |

| Johne’s Disease | Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis | Chronic diarrhea, wasting | No anemia, which occurs in older animals, was confirmed via PCR/ELISA |

| Nutritional Issues | Deficiencies (e.g., cobalt, protein) | Poor coat, weight loss, reduced performance | No parasites in feces; responsive to dietary supplementation |

| BVD (Bovine Viral Diarrhea) | Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus | Diarrhea, mucosal lesions, and immunosuppression | Lab tests (PCR/ELISA), possible mucosal ulceration |

| Abomasal Disorders | Displacement/impaction | Anorexia, bloating, reduced motility | Clinical exam, auscultation, imaging, or surgical exploration |

Pathogenesis

Ostertagia infections cause significant biochemical and pathological changes in the abomasum:

The destruction of parietal cells leads to a rise in abomasal pH (up to 7.0), impairing digestion.

Leakage of pepsinogen into circulation results in elevated plasma pepsinogen levels.

Protein loss in the gastrointestinal tract leads to hypoalbuminemia and submandibular edema.

The abomasal mucosa thickens, forming nodules, and can resemble “morocco leather” in severe cases.

Clinical Signs

Ostertagiosis occurs in two clinical forms:

Type I Ostertagiosis (Summer)

Affects calves during their first grazing season (July-October in the Northern Hemisphere).

Symptoms: Profuse, bright green diarrhea, weight loss, inappetence.

High morbidity (>75%) but low mortality with prompt treatment.

Type II Ostertagiosis (Winter-Spring)

Affects yearlings due to arrested larvae from the previous autumn.

Symptoms: Intermittent diarrhea, anorexia, thirst, dull coat, and rapid weight loss.

There is a lower prevalence but high mortality if untreated.

Epidemiology

Ostertagia ostertagi, the brown stomach worm, is a dominant gastrointestinal nematode in cattle, with related species like O. circumcincta affecting sheep and O. gruehneri in wild ruminants. Recent studies highlight its prevalence in temperate regions, driven by moist climates that favor larval survival. Research from 2023–2025 shows rising infection rates in areas like northern Europe and North America due to climate change, which extends grazing seasons and larval persistence. For instance, a 2024 study in Canada reported O. ostertagi in 65% of sampled dairy herds, linked to warmer, wetter springs. In contrast, low prevalence in arid regions or isolated populations (e.g., Greenland caribou) suggests that host density and environmental barriers limit spread.

Economic Impact

Ostertagia infections significantly affect livestock production:

Reduced weight gain and poor feed conversion rates.

Decreased milk yield in lactating cows.

Increased veterinary costs due to anthelmintic treatments.

Diagnostic Innovations

Diagnosing Ostertagia is challenging due to variable egg shedding, especially in adults. Modern advancements include:

- Molecular Diagnostics: PCR assays targeting O. ostertagi ITS-2 genes offer high sensitivity, detecting infections missed by traditional fecal egg counts (FECs). A 2024 study validated a qPCR panel for mixed nematode infections.

- Biomarkers: Serum pepsinogen and abomasal IgE levels correlate with worm burdens, with new ELISA kits improving field diagnostics.

- Digital Tools: Machine learning models, trained on FEC and biomarker data, predict infection risk, aiding targeted treatments.

Treatment and Control

Effective treatment and control strategies include:

Anthelmintic Treatment:

Benzimidazoles, macrocyclic lactones (ivermectin, doramectin), and imidazothiazoles (levamisole) are highly effective against both adult and larval stages.

Targeted deworming at critical times, such as pre-grazing, mid-season, and pre-housing, helps break the parasite’s life cycle.

Resistance management strategies, such as rotating drug classes and using combination treatments, reduce the risk of anthelmintic resistance.

Immunity and Vaccine Research

Host immunity involves mucosal IgA and Th2 cytokine responses, but Ostertagia evades these through immunosuppressive secretions. Recent studies (2023–2025) explore:

- Antigen Targets: Larval glycoproteins and proteases show promise in experimental vaccines, reducing worm counts by 30–40% in trials.

- Immune Modeling: Repeated low-dose infections induce partial immunity, with a 2024 study showing elevated IgG and reduced egg output after controlled exposures.

- Challenges remain, as co-infections and host variability hinder consistent vaccine efficacy.

Grazing Management:

Rotational grazing minimizes reinfection by preventing the buildup of infective larvae in pastures.

Mixed-species grazing can help reduce parasite burden, as some species act as dead-end nematode hosts.

Nutritional Support:

Providing high-protein diets helps counteract protein loss due to parasitism.

Supplementing with minerals such as cobalt, copper, and selenium boosts immune function and resilience to infection.

Integrated Parasite Control:

Combining anthelmintic treatment with pasture management and selective breeding for parasite-resistant animals enhances long-term control.

Regular fecal egg counts help monitor parasite loads and inform treatment decisions.

Cutting-Edge Research

- Microbiome Interactions: A 2025 study linked Ostertagia infections to altered gut microbiota, reducing beneficial bacteria and exacerbating malnutrition.

- Climate Modeling: Predictive models assess how warming climates shift Ostertagia risk, guiding regional control strategies.

Future Directions

Research is pivoting toward sustainability, with emphasis on:

- Vaccine Development: mRNA-based vaccines are in early trials, inspired by COVID-19 platforms.

- Smart Farming: IoT-enabled monitoring systems for real-time parasite surveillance.

- One Health Approaches: Addressing Ostertagia alongside other zoonotic and production diseases to optimize livestock health.

Zoonotic Shadows: Assessing Human Risk

Ostertagia ostertagi is not a known zoonotic parasite, as it is highly adapted to ruminant hosts. However, recent studies (2024) caution that its genetic proximity to zoonotic nematodes, like Trichostrongylus, warrants monitoring. In regions with intensive livestock farming and poor sanitation, there’s a theoretical risk of rare cross-species transmission, particularly to immunocompromised individuals handling infected animals or contaminated soil. Public health research emphasizes surveillance in rural settings to detect any spillover, though no human cases have been documented, keeping Ostertagia a low-priority zoonotic concern.

Safeguarding Food Systems

Ostertagia infections reduce livestock productivity, impacting food safety and availability, a critical public health issue. Subclinical infections decrease milk production by 5–10% and lower meat quality, straining food supply chains, especially in developing nations. A 2025 study found that infected dairy herds produce milk with elevated somatic cell counts, increasing risks of bacterial contamination if processing standards are lax. Public health measures focus on farm-level parasite control, such as regular deworming and pasture management, to ensure safe, high-quality animal products and maintain food security for vulnerable populations.

Economic Strain on Community Well-Being

Recent estimates (2024) peg global losses at $1.8 billion annually due to reduced herd productivity, hitting smallholder farmers hardest. This financial strain limits access to healthcare, nutrition, and education, deepening health inequities. Public health initiatives, like a 2024 program in South Asia, show that subsidized anthelmintic treatments and farmer training can boost cattle yields by 15–20%, enhancing household income and community health resilience.

Resistance Risks in the AMR Crisis

Anthelmintic resistance in Ostertagia, reported in 25% of 2025-tested cattle herds, parallels the broader antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis, a major public health challenge. Overuse of drugs like ivermectin contributes to resistant parasite strains, potentially sharing resistance mechanisms with other pathogens. Environmental residues from anthelmintics also disrupt soil ecosystems, which could indirectly affect human health through food chains. Research pushes for targeted treatments, using diagnostics like qPCR to guide deworming, reducing drug reliance, and aligning with global AMR strategies.

One Health Integration

Modern research frames Ostertagia control within a One Health approach, linking animal, human, and environmental health. A 2025 study piloted an integrated model combining Ostertagia management with other livestock diseases, reducing chemical use and resistance risks. This approach minimizes residues in milk and meat, ensuring safer food, while sustainable practices like nematophagous fungi cut larval loads without environmental harm. Public health benefits include stronger food systems and reduced AMR, with ongoing trials scaling these strategies in mixed farming communities.

Conclusion

Ostertagiosis remains a major challenge in ruminant health worldwide. Implementing strategic anthelmintic treatment, proper grazing management, and nutritional support can minimize economic losses and improve animal welfare.

FAQ’s

What animals are affected by Ostertagia?

Ostertagia primarily infects ruminants, including cattle, sheep, and goats. The most common species are Ostertagia ostertagi in cattle and Ostertagia circumcincta in sheep and goats.

2. What is Ostertagia’s predilection site?

The abomasum is the primary site of infection. Larvae embed in the gastric glands, while adults reside on the mucosal surface.

3. What are the symptoms of Ostertagia infection?

Symptoms include diarrhea, weight loss, poor growth, and reduced appetite. In severe cases, animals may develop a “bottle jaw” due to fluid accumulation.

4. How is Ostertagia diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves clinical signs, fecal egg counts, plasma pepsinogen levels, and post-mortem examination of the abomasum.