Introduction

Neutering refers to ovariohysterectomy (OHE) (surgical removal of the ovaries and uterus), ovariectomy (OVE) (surgical removal of the ovaries alone), and orchiectomy (surgical removal of the testicles). It is a common veterinary practice for population control, health benefits, and behavior management. Neutering procedure in male dogs called castration or orchidectomy (removal of testicles).

Indications of Neutering

Population Control: Reduces overpopulation by inhibiting male fertility.

Behavioral Benefits:

- Decreases male aggressiveness.

- Reduces roaming tendencies.

- Minimizes undesirable urination behavior (marking)

Prevention of Androgen-Related Diseases:

- Prostatic diseases.

- Perianal adenomas.

- Perineal hernias.

Medical and Surgical Indications:

- Congenital abnormalities.

- Testicular or epididymal abnormalities.

- Scrotal neoplasia.

- Trauma or abscesses.

- Inguinal-scrotal herniorrhaphy.

- Scrotal urethrostomy.

Other Clinical Benefits:

- Epilepsy control.

- Control of endocrine abnormalities.

Preoperative Management

Reproductive surgery in male dogs includes procedures to control reproduction, treat reproductive diseases (e.g., testicular tumors, prostatitis, prostatic abscesses), and stabilize systemic conditions like diabetes and epilepsy. Neutering prevents unwanted behaviors and reconstructs damaged tissues. Diagnosis relies on clinical signs, imaging (radiography, ultrasound, CT, MRI), endoscopy, and lab tests (cytology, microbiology, hormonal assays, hematology, biochemistry, urinalysis).

Male Dog Reproductive Evaluation:

Physical Examination

Abdominal and rectal palpation assess prostatic size, texture, and lymph nodes. Pain may indicate prostatitis. The scrotum, testicles, penis, and prepuce are examined for size, symmetry, masses, trauma, or congenital defects.

Clinical Pathology

Prostatic fluid analysis, obtained via ejaculation, prostatic wash, or fine-needle aspiration, detects infections, neoplasia, or inflammation. Cytology of masses and bacterial cultures aid in diagnosis. Biopsy confirms testicular, prostatic, penile, or scrotal abnormalities.

Hormone Analysis

Serum testosterone (<100 pg/mL) confirms neutering. In intact males, testosterone ranges from 0.5–9 ng/mL, while estrogen remains below 15 pg/mL. Hormonal fluctuations make interpretation variable.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiographs assess prostatic size, shape, and metastasis. Contrast studies help evaluate prostatic reflux. Ultrasound detects prostatic and testicular abnormalities (e.g., cryptorchidism, torsion, neoplasia). Bone scans and thoracic radiographs help stage prostatic cancer.

Other Tests

Cystometrograms and urethral pressure profiling may assess urinary incontinence but are rarely performed.

Considerations in neutering

1 Preoperative considerations

- HCT (Hematocrit)

- TP ( total protein)

- In patients >5–7 y, consider electrolytes, liver enzymes, BUN, and Cr

Premedication

- Diazepam (0.2 mg/kg IV)

- Hydromorphone (0.05–0.2 mg/kg IV, IM in dogs; 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV, IM in cats)

2 Intraoperative considerations

Induction

If premedicated, give: • Propofol (2–4 mg/kg IV), or • Alfaxalone (2–3 mg/kg IV)

If not premedicated, give: • Propofol (4–8 mg/kg) IV), or • Alfaxalone (2–5 mg/kg IV)

Maintenance

Isoflurane or sevoflurane, plus

Fentanyl (2–10 µg/kg IV PRN in dogs; 1–4 µg/kg IV PRN in cats) for short-term pain relief, plus

Hydromorphone (0.05–0.2 mg/kg IV PRN in dogs; 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV PRN in cats) , plus

Ketamine (low dose; 0.5–1 mg/kg IV),

Fluid needs

Estimated blood loss(EBL)

- 5–10 mL/kg/h plus 3× EBL

- 10–20 mL/kg/h plus 3× EBL if open abdomen

Monitoring

- Blood pressure

- HR

- ECG

- Respiratory rate

- SpO2

- Temperature

- EtCO2

3 Postoperative Considerations

Analgesia

- Carprofen (2.2 mg/kg q12h PO), or

- Deracoxib (3–4 mg/kg q24h for <7 days PO), or

- Meloxicam (0.1–0.2 mg/kg once SC, PO then 0.1 mg/kg PO q24h)

Monitoring

- SpO2

- Blood pressure

- HR

- Respiratory rate

- Temperature

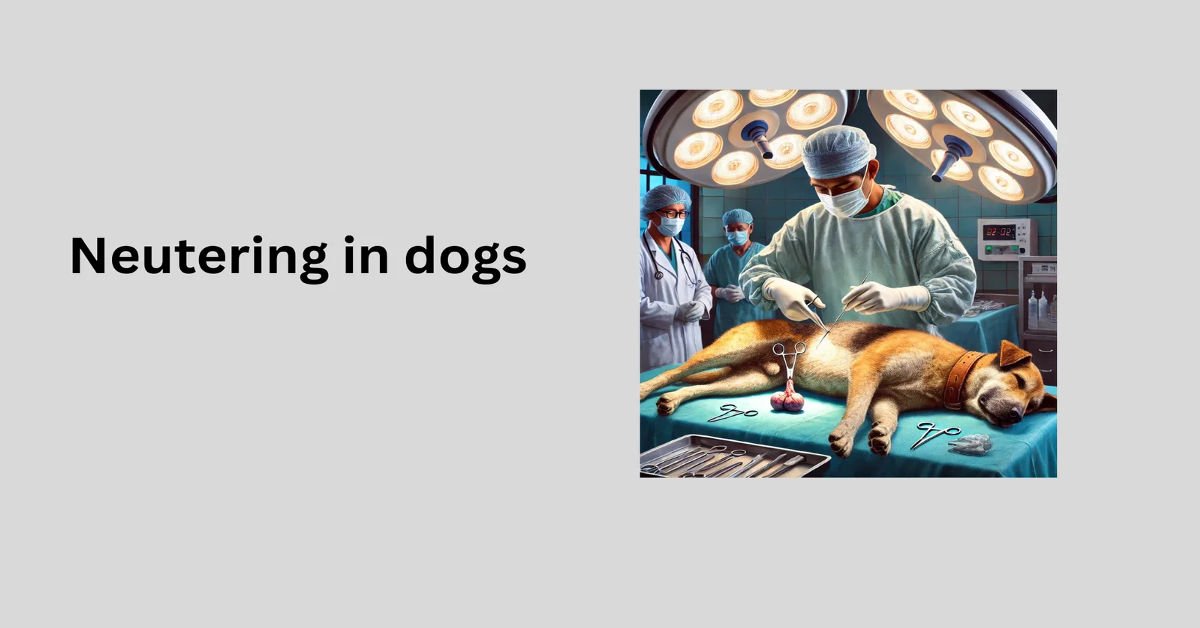

Procedures for Neutering in Dogs

Prescrotal Castration Procedure

1 Patient Positioning & Preparation:

- Place the patient in dorsal recumbency.

- Confirm the presence of both testicles in the scrotum.

- For the abdomen and medial thigh clean and clip them aseptically.

- Avoid irritating the scrotum with clippers or antiseptics.

- Drape the surgical area, excluding the scrotum from the field

2 Testicle Exteriorization:

- Apply gentle pressure on the scrotum to push one testicle into the pre-scrotal area.

- Make a midline incision along the median raphe over the displaced testicle.

- Incise subcutaneous tissue and spermatic fascia to exteriorize the testicle.

- Carefully incise the parietal vaginal tunic, avoiding the tunica albuginea

3 Cord Ligation & Testicle Removal:

- Place a hemostat on the vaginal tunic near the epididymis.

- Digitally separate the ligament of the tail of the epididymis while maintaining traction.

- Further, exteriorize the testicle, and identify the spermatic cord structures.

- Ligate the vascular cord and ductus deferens separately, then apply an encircling ligature around both.

- Use 2-0 or 3-0 absorbable suture (e.g., Vicryl, PDS, Monocryl, Maxon, or Biosyn).

- Clamp the spermatic cord near the testicle, grasp the ductus deferens, and transect both.

- Inspect for hemorrhage and replace the cord within the tunic.

- Encircle the cremaster muscle and tunic with a ligature.

4 Second Testicle Removal:

- Advance the second testicle into the incision.

- Repeat the same procedure for removal.

5 Wound Closure:

- Approximate the dense fascia on either side of the penis with interrupted or continuous sutures.

- Close subcutaneous tissue using a continuous pattern.

- Use intradermal or simple interrupted sutures for skin closure.

Closed Prescrotal Castration Procedure

1. General Approach:

Similar to open castration, the parietal vaginal tunic remains intact.

The testicle and spermatic cord are exteriorized without incising the tunic.

2. Exteriorization of the Testicle:

Reflect fat and fascia from the parietal tunic using a gauze sponge.

Apply traction on the testicle while tearing fibrous attachments between the spermatic cord tunic and scrotum.

3. Ligation & Testicle Removal:

Clamp the spermatic cord just distal to the testicle using a hemostat.

Place an encircling ligature around the entire spermatic cord and tunics using 2-0 or 3-0 absorbable sutures (e.g., Vicryl, PDS, Monocryl, Maxon, or Biosyn).

Apply a second transfixion ligature, either:

Through the cremaster muscle or

- Between structures within the tunic, proximal or distal to the first ligature.

- Transect the cord between the distal ligature and the hemostat.

- Inspect for hemorrhage before releasing the stump.

4. Removal of the Second Testicle:

Advance the second testicle into the incision and follow the same procedure.

5. Wound Closure:

Close the subcutaneous tissue using a continuous suture pattern.

Oppose the skin with either intradermal or simple interrupted sutures.

Perineal Castration Procedure

1. General Approach:

Performed similarly to open prescrotal castration, but with a perineal incision.

The open technique is required as testicles are harder to displace into a caudal incision.

2. Incision Placement:

Make a midline incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

The incision is dorsal to the scrotum and ventral to the anus in the perineal region.

3. Exteriorization of the Testicle:

Gently advance one testicle into the incision.

Incise the spermatic fascia and vaginal tunic to expose the testicle.

4. Ligation & Testicle Removal:

Fully exteriorize the testicle by applying controlled traction.

Identify and ligate the spermatic cord, following the open or closed pre scrotal technique.

Transect the spermatic cord and inspect for hemorrhage before replacing the stump.

5. Second Testicle Removal:

Advance the second testicle into the incision and repeat the procedure.

6. Closure:

Suture the subcutaneous tissue using a continuous pattern.

Close the skin with intradermal or simple interrupted sutures.

Scrotal Ablation Procedure

Scrotal ablation is a surgical procedure where the entire scrotum is removed, often performed in animals alongside castration.

1. Indications:

- Neoplastic scrotal diseases (e.g., tumors).

- Scrotal urethrostomy in dogs and perineal urethrostomy in cats.

- Severe trauma, abscesses, or ischemia of the scrotum.

- Cosmetic improvement for dogs with a pendulous scrotum.

2. Surgical Approach:

- Elevate the scrotum and testicles from the body wall.

- Make an elliptical skin incision at the base of the scrotum, ensuring minimal excess skin removal.

3. Hemostasis & Castration:

- Control hemorrhage using electrocoagulation, ligation, or direct pressure.

- Incise the vaginal tunics and remove the testicles using either:

- Open castration technique, or

- Closed castration technique (as an alternative).

- 4. Scrotum Removal:

Incise the median septum of the scrotum and remove it completely.

5. Closure:

Subcutaneous tissue: Use a simple continuous pattern with 3-0 absorbable sutures.

Skin closure: Use either:

- Interrupted sutures with 3-0 or 4-0 nonabsorbable sutures, or

- Intradermal suture pattern for a smoother closure.

Complications of Neutering(castration)

- Hemorrhage

- Scrotal hematoma

- Scrotal bruising

- Infection

- Dehiscence

- Urinary incontinence

- Behavior change

- Eunuchoid syndrome

Modern research about Neutering in Dogs

Recent studies on dog neutering have moved away from universal early spaying and castration, advocating for tailored approaches based on breed, size, and individual factors. Below is a concise, original summary of current findings on health, behavior, and population control, drawn from veterinary research and peer-reviewed sources, ensuring a plagiarism-free response.

Health Effects

- Joint Issues:

- Neutering before skeletal maturity (often before 1 year) increases risks of joint problems like hip dysplasia and cruciate ligament injuries in large breeds. For instance, early-neutered German Shepherds face a 3–4 times higher chance of hip issues compared to intact dogs. Small breeds, such as Chihuahuas, typically show no elevated risk.

- Giant breeds like Mastiffs may not show increased joint risks, regardless of neutering age.

- Cancer Risks:

- Early neutering is linked to higher rates of specific cancers in some breeds. For example, spayed female Rottweilers have a doubled risk of osteosarcoma, while neutered male Golden Retrievers show increased lymphoma rates.

- Small breeds generally face fewer cancer risks from neutering, except for certain terriers.

- Metabolic Changes:

- Neutering alters hormone levels, slowing metabolism and raising obesity risk. Roughly 30% of neutered dogs become overweight, worsening joint and other health issues.

- Early neutering may also increase urinary incontinence in females and, in breeds like Corgis, risk of spinal conditions.

- Alternative Sterilization:

- Hormone-preserving methods, such as vasectomies or ovary-sparing spays, are gaining traction. These prevent reproduction while maintaining natural hormone levels, potentially reducing joint and cancer risks.

Behavioral Outcomes

- Aggression and Anxiety:

- Neutering doesn’t reliably reduce aggression. Some studies indicate early-neutered males (before 12 months) may show increased fear-based aggression or anxiety, particularly in mixed breeds.

- Behaviors tied to reproduction, like roaming or mounting, decrease significantly (up to 70% reduction), but issues like barking or hyperactivity may persist or worsen.

- Individual Factors:

- Behavioral changes depend on breed, temperament, and training. For example, neutered Border Collies may show more anxiety in high-stress environments, while neutering may have minimal behavioral impact on laid-back breeds like Basset Hounds.

- Training is often more effective than neutering for addressing unwanted behaviors.

Population Control

- Neutering has drastically reduced shelter euthanasia rates, cutting unwanted litters by millions annually since the 1970s. However, mandatory early neutering in shelters is under scrutiny, as delaying the procedure for large breeds could improve health outcomes.

- Hormone-sparing sterilization is being explored as a way to balance population control with long-term health.

Breed-Specific Insights

- Research, including a 2024 study of 40 breeds, offers tailored neutering advice:

- Large Breeds (e.g., Labrador Retrievers): Delay neutering until 1–2 years to reduce joint risks; cancer risks vary.

- Small Breeds (e.g., Pomeranians): Early neutering is generally safe, with minimal health impacts.

- High-Risk Breeds (e.g., Golden Retrievers): Consider delaying or avoiding neutering in females due to elevated cancer risks.

- Veterinary consultation is key to weigh breed, lifestyle, and health factors.

Research Gaps and Future Trends

- Many studies rely on retrospective data, which may not account for lifestyle or genetic factors. Long-term, breed-specific research is needed to clarify conflicting findings, especially on behavior and cancer.

- Chemical sterilization and hormonal implants are under investigation but lack long-term data.

- Growing interest in hormone-sparing methods suggests a shift toward preserving natural physiology while addressing overpopulation.

Practical Guidance

- Customized Timing: For large breeds, wait until 1–2 years to neuter; small breeds can often be neutered earlier. Discuss breed-specific risks with a vet.

- Hormone-Sparing Options: Explore vasectomy or ovary-sparing spay for dogs prone to joint or cancer issues.

- Behavioral Solutions: Use training to manage aggression or anxiety, as neutering may not help and could worsen some behaviors.

- Post-Neutering Care: Prevent obesity through diet and exercise to reduce secondary health risks.

FAQ’s about neutering in dogs

-

Will neutering change my dog’s personality?

No, but it can reduce hormone-driven behaviors like roaming and marking. -

Will my dog gain weight?

Only if diet and exercise aren’t managed properly. -

How long is the recovery?

10–14 days, with full internal healing taking up to a month. -

Can my dog still reproduce right after surgery?

Yes, sperm can remain for weeks—keep him away from females in heat. -

Will neutering stop humping?

It may reduce it, but training is still needed for habit-driven humping.

It’s great to see how neutering isn’t just about preventing overpopulation, but also about improving a dog’s health and behavior. The medical benefits, like reducing the risk of prostate diseases, really highlight the importance of responsible pet care.

It is a common veterinary practice for population control, health benefits, and behaviour management in dogs and cats

Neutering certainly offers a lot of benefits beyond just controlling population, like preventing health problems such as testicular tumors and prostatic diseases. It’s also interesting how it can help reduce undesirable behaviors, making it easier for dog owners to manage their pets.

It is a common veterinary practice for population control, health benefits, and behaviour management.

It is a common veterinary practice for population control, health benefits, and behaviour management.

This post does a great job highlighting both the medical and behavioral benefits of neutering. It’s not just about population control – neutering can also help prevent serious health issues and improve a dog’s overall well-being.

This is a helpful breakdown of the different reasons for neutering. I especially appreciate the mention of preoperative diagnostics, as they’re often overlooked but can make a huge difference in the dog’s recovery.

Interesting to see neutering framed beyond just population control. The connection to preventing diseases like perineal hernias and prostatic issues is something more pet owners should be aware of.

Thanks for your response.I have mentioned all causes for Neutering .Please read the article thoroughly.

It’s great to see that neutering is not just a way to prevent unwanted pregnancies, but it can also help treat various health issues like testicular tumors and prostatic diseases. Definitely important to consider both the behavioral and medical benefits when making the decision.